The Birth of a Fil-Am Artist Collective

From studio conversations to a landmark exhibit in Little Tokyo, Bonnie Ho chronicles how a group of Filipino American artists reclaimed space, identity, and history through collaboration.

At a small gathering in an art studio space, Diane Briones Williams, a mixed media artist, found herself talking about the concept of collectives.

“I wanted to meet other Filipino visual artists and people who could relate to the feeling of having more of a connection to their ethnicity and lineage.” As a FilAm artist, Diane also said, “we needed to be seen more.”

She told a person at the gathering that she did not know many other FilAm artists in L.A.

“Why don’t you talk to Michael Rippens?” that person suggested, referring to a local Filipino American multidisciplinary artist.

Recalling this exchange, Diane laughed. She already knew Michael. It was then she realized she knew a number of FilAm artists — they just weren’t organized based on their shared identity and interests. Diane and Michael reached out to other artists, one by one growing their community.

In 2023, Naman was born, a L.A.-based collective representing transpacific Filipinx artists and cultural workers.

The inaugural art show

This March, Naman launched its inaugural group show at the nonprofit art space LA Artcore in Little Tokyo. Featuring a unique combination of art across disciplines, the show included, among other mediums, musical performance, woven sculptures, and a telephone receiver one could listen to, an example of social practice (interactive or participatory art).

Letitia F. Ivins, an arts administrator for Naman, said a key message from the show was, “Don’t try to put us in a box — we all have our multiple identities and ways of being and practices.” She added, “but we do share a longing for the homeland and culture, since most of us are FilAm.”

“There is a reaching for our heritage, origin, our ancestors, which happens through research — from learning about indigenous culture erased from curriculum and from parents about our community.”

Together the pieces recognized and celebrated FilAm multifaceted identities and examined history, calling out narratives stemming from Spanish and U.S. colonialism.

A longing for homeland and family

A plain wooden bench only exists as an optical illusion through a reflection. People at the show are carefully warned not to try to sit on it.

“Bangko” benches are found along sidewalks and street corners in the Philippines. For interdisciplinary artist Aaron Panela Dadacay, who was born in the Philippines, this piece represents nostalgia for its street culture.

In his statement about the piece, Aaron noted that these benches were where “groups of people loiter and exchange daily news and gossip” about the neighborhood.

But the mirror that makes the bench appear real represents how memories can be distorted over time into a false sense of reality. Accordingly, Aaron made the shape of the mirror to resemble the painted tunnels the mischievous cartoon character Wile E Coyote used to trick prey.

Connection to family and inheritance were also themes in the show.

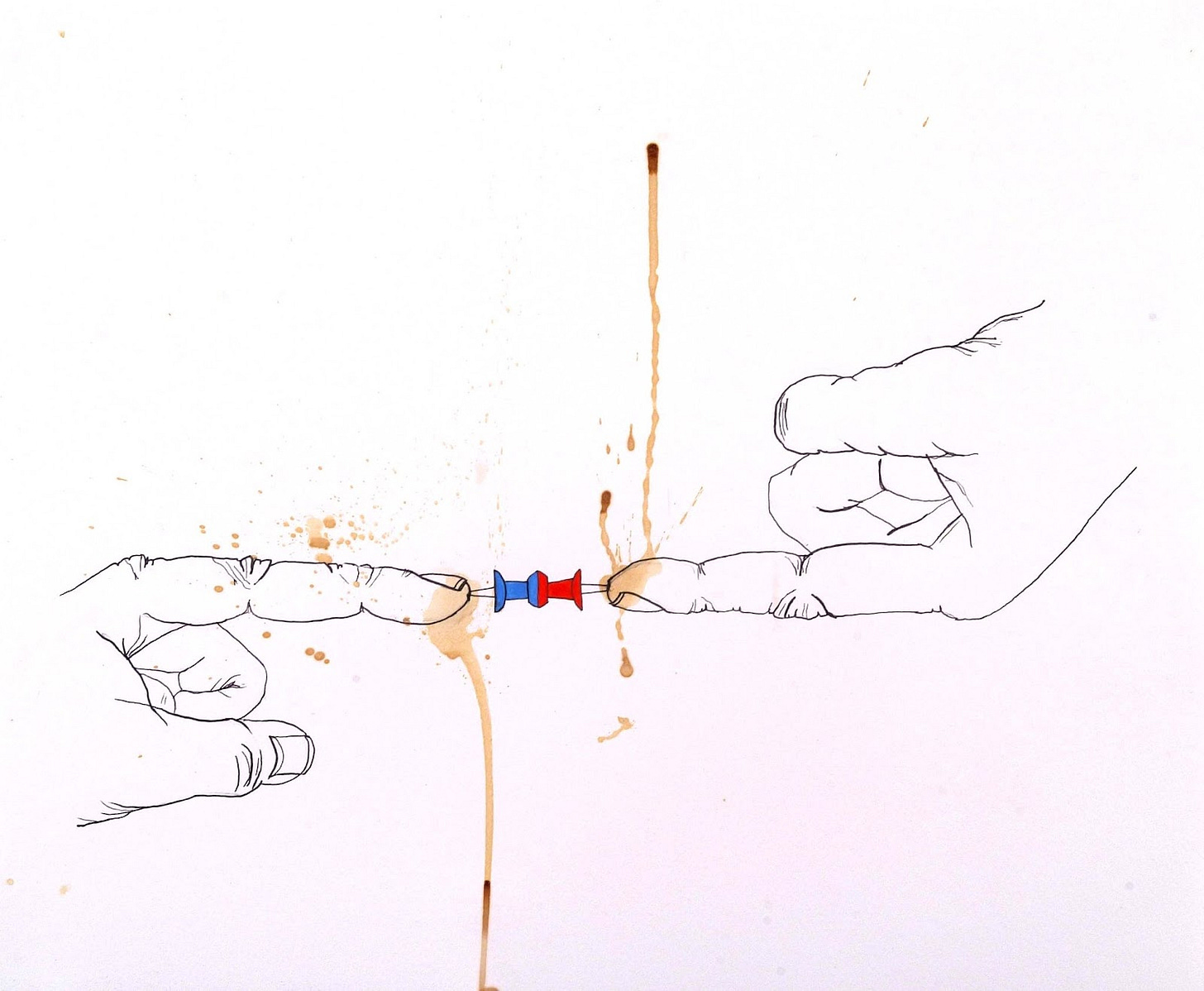

In a narrow corridor, viewers came face to face with a series of drawings of fingers being pierced by sharp objects. Another attendee and I both agreed that this series was hard to look at for long — one almost experienced the pain secondhand.

During the artist walkthrough, Christine Morla explained that she created these pieces to grapple with the pain she was witnessing and experiencing while her father was dying.

The series was about “testing one’s threshold for pain,” Christine wrote in her statement about the series. The series also spoke to the qualities one inherits. “We carry our ancestors forward with our hands not only in the physical traits, but more importantly the resilience, perseverance and continuance of tradition.”

References to FilAm history

Diane pointed out that Naman’s inaugural show location is significant because the area of Little Tokyo was formerly known as Little Manila.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the area was considered a thriving Filipino American community, but over time, the community migrated during redevelopment of adjacent areas. (The Westlake area today known as Historic Filipinotown, officially recognized in 2002, represents the Filipino American community in L.A. from the 1950s onward.)

Diane said researching history has been integral to her art practice. At the inaugural show Diane’s wall-hangings and sculptural weaving incorporated indigo-dyed fibers, the major agricultural export from the Philippines for the Spanish empire.

Even though retracing history’s sequence of events — such as colonialism or racism —is painful, Diane chooses to do so.

“It’s important to read about history because it reflects our present, reflects what’s happening today.”

In one corner of the show, two walls are covered with intricately designed wallpaper. At close glance, the wallpaper pattern displays grotesque nineteenth-century political cartoons to convey American attitudes towards the Philippines during U.S. imperialist expansion.

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza said for this piece, “If these walls could talk,” she created the type of space that wasn’t made for her. Maryrose observed how historically particular people in leadership roles felt free to say derogatory and racial things behind closed doors, in places like board rooms.

“They did this with their agenda for the annexation of the Philippines. If you were in the room, this is what you’d hear,” Maryrose said.

The only difference today, she noted, is U.S. political leaders aren’t even disguising their dismantling of D.E.I. programs.

As part of this scene, a small sculpted figure, maliit guardian, sits facing the wallpaper, a reference to a rice god. Maryrose said it is “like a guardian standing by.”

A collective as a safe space to take risks

Following the inaugural show, Naman organized a “story circle,” inviting civic leaders with experience organizing artists to discuss the history of L.A.’s Filipinx arts representation, community-building, and cultural organizing.

At the event, Letitia heard that “the value of a collective is having a space for dialogue, to bounce ideas around the broader social issues that may be affecting the culture of the community and the community at large.”

Letitia also noted that a collective is where people come together with a common understanding, which creates a space for joy and laughter. This safe space also allows for “honest critique as a form of generosity and care.”

Being part of a collective, too, provides cover to make stronger statements.

A leader at the event shared an example of how, following the 1990s riots, a collective made provocative art for L.A. City Hall that was met with some resistance. Because they were a collective, instead of a single artist or formal institution, they had a certain degree of freedom in advocating for the artwork.

Letitia said the organizers posed this question and imparted this advice: “how do we leverage our collective power to make statements about social issues that matter to us? Don’t be afraid. Be willing to take risks.”

Showing up for one another

When asked about the group’s next steps, Diane said they will continue to advocate for one another, raise the visibility of FilAm artists, and support one another’s interests, whether it be for shows and programs or for those with interests in social justice and advocacy.

Already, being with other FilAm artists and having their support has made a difference for Maryrose.

In 2024, Naman members attended an exhibition — Filipino California: Art and the Filipino Diaspora — where a few fellow members, Maryrose, Maria Villote, and Christine Morla, were showcasing their art. After the show at Forest Lawn Museum, the Naman group shared a meal together.

Raising that she is among the oldest in the group, Maryrose said, “I learn a lot from the younger generation, being in their company, listening to how they do things.”

“Being part of this community has helped me personally. I feel genuinely happy to be part of this group.”

More photos from the show

About the Author:

Bonnie Ho is Chinese American and a former drawing student of the artist Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza. She is interested in supporting efforts to advance equity, engaging with communities, and storytelling.